Acclaimed author of ‘American Born Chinese’ visits CHS

It’s not every day that students get a chance to look inside of the mind and motivations of an award-winning author as well as a more in-depth look into the world of comics.

However, when Gene Luen Yang, the author of several graphic novels and comic books, including the 2016 National Book Award finalist American Born Chinese, visited CHS on November 4 and 5, they were able to do that and much more.

Eliza Park, a ninth-grade English teacher at CHS, was responsible for bringing Yang to the students. She got the idea for the author to visit after viewing another speaking engagement he gave.

“A few years ago, I watched a TED Talk given by Gene Luen Yang and I was inspired to see if he would come to CHS,” said Park. “I wanted all the ninth graders to have this once-in-a-lifetime experience of reading a book and then immediately getting to meet the author.”

Park added, “It’s such a powerful thing – to have questions about the book and to then get to literally ask those questions to the author of the book. I wanted every single ninth-grader, regardless of level or teacher or any of that, to be able to meet him and hear him speak.”

Park reached out to Yang’s event manager about coming to CHS, who told her that Yang did give talks to high school students. Determined to get Yang to visit, Park then began raising money to pay for the author’s expenses.

“His events manager got back to me and told me that yes he does, and she gave me the cost, $10k plus expenses once here, and then I just had to raise that money,” said Park. “I applied for a whole bunch of grants to help defray the cost. That took the most time, and not every grant application worked out. After a lot of work, I had lined up $5,000 from the Bison Foundation and $5,000 from Kappa Delta Pi at Dickinson to cover the costs of the visit!”

Yang’s first event was an assembly with the entire ninth grade class, which took place in the Swartz auditorium. The author discussed the plotlines of his graphic novel, American Born Chinese, with the students, all of whom read the book in their English classes as part of the school curriculum, including the aspects of the lives of his parents and relatives that he drew upon to write the novel.

“Jyn [the main character of American Born Chinese]’s parents come to America for graduate school, just like my parents did,” Yang described to the students. “Jyn’s parents meet in a university library. That’s exactly how my parents met; they met in the university library. Nerdiness runs deep in my family.”

Yang also drew upon his own experiences for the book, some of which were negative.

“A lot of the most culturally inappropriate things said in the book are said by this kid, Timmy,” Yang said. “At my junior high, there was a group of kids we used to call the stoners. They would go to the back parking lot of my school after school and do these really terrible things. Whenever this group of stoners, and my group of friends–I used to hang out with a small group of Asian-American boys–whenever we would pass each other in the halls, they would always yell something racist at us. I took a lot of the words I heard in the hallways of my junior high, and I stuck them in the mouth of my character Timmy.”

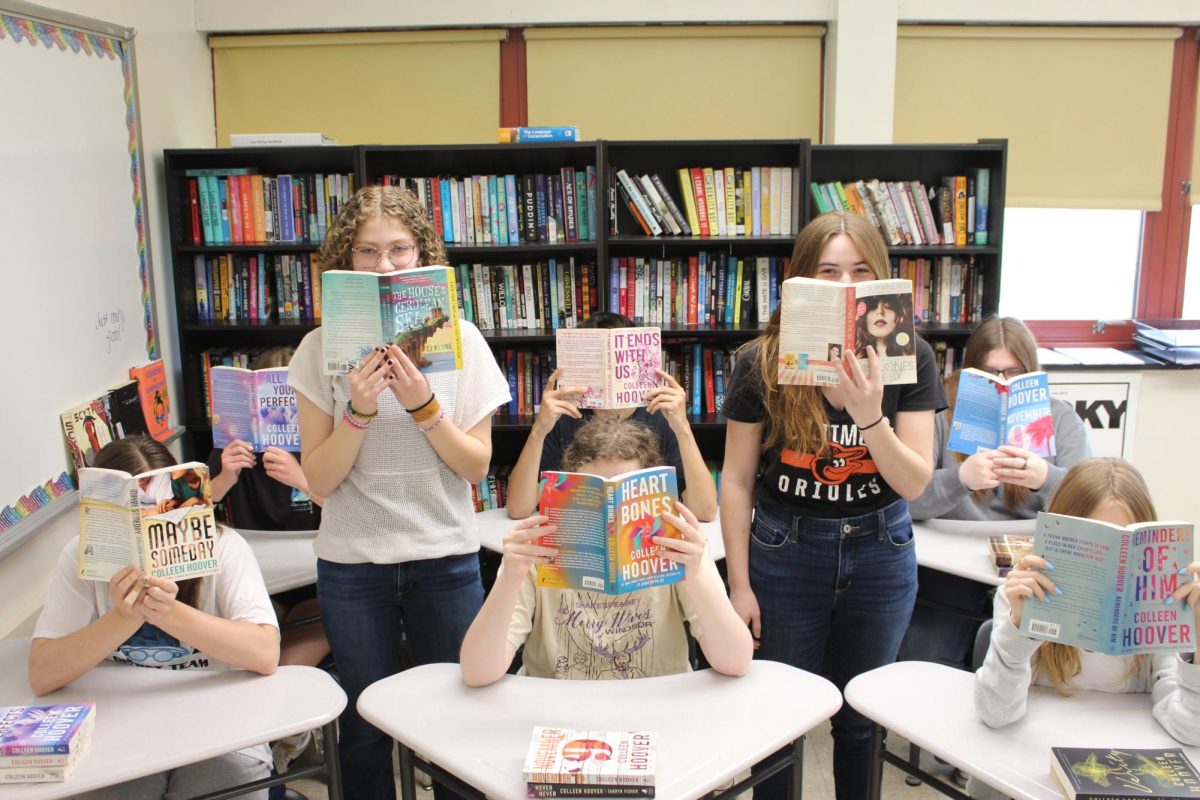

The author symposium with Yang, held on Tues Nov 5, was much smaller than the ninth grade assembly, with only a couple dozen students attending. These students, who were handpicked through the event after completing applications, spanned all four grade levels and discussed the history of Asian-Americans in comics, as well as how a writer’s heritage can impact the stories they choose to tell.

“He talked about the history of Asian-Americans in the comic book world, and how they changed a lot about how Asian-Americans were portrayed,” Juniper Bates, a freshman who attended both the ninth grade assembly and the symposium, said. “I knew about yellow peril villains, but it opened my eyes to a lot of that happened in the comics and the [comic] offices.”

Yang’s discussion of heritage and comic book characters included descriptions of Asian-American comic book characters, including members of the G.I. Joe franchise, as well as some created by Jewish-American comic book creators during the 1940s-60s. The most famous of these examples was, by far, Superman; the Man of Steel was created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, two children of Jewish immigrants.

“They definitely put parts of their own cultural experiences into Superman,” Yang told the students. “Superman is a cultural analog for the Jewish-American experience.”

The emphasis on diversity in media, and especially representation for people descended from immigrants, was something Park believed was extremely important for CHS students to hear.

“American Born Chinese is about the marginalized experience of Americans with immigrant parents, and that’s such a critical lived experience for many of our students here in Carlisle,” said Park. “We have a large immigrant population, and I feel strongly that those students need to be represented in our curriculum. Non-immigrants can also build empathy through reading about those experiences.”

Grace Pak, a freshman who attended the ninth grade assembly, the symposium, and a talk given by Yang at Dickinson College, said the points Yang made about diversity in the media were extremely important, especially in regards to younger audiences.

“I think that it’s important for a diverse group of people to be shown in the media because people, especially children, need someone to look up to like a role model,” said Pak. “When those of different heritage look to the media [for role models], and see only white people, it can make them feel unworthy or not enough.”

Pak was extremely interested in what Yang had to say about his experiences as the child of immigrants.

“He was a great speaker, and as a Korean-American, it was really interesting to hear all that he had to say,” said Pak. “My dad went with me to the Dickinson event, and he enjoyed it as well because his dad was an immigrant. All around, it was just very interesting, with what he had to say as a writer, an artist, and as a Chinese-American.”

Although all three events did discuss Yang’s experiences as a Chinese-American and mentioned his work on American Born Chinese and his other novels, the events did differ in terms of format and subject matter beyond these aspects.

“At [the symposium], he took way more questions, and most of them were about his process as a writer and how he draws the pictures,” said Pak. “It was great for people who want to go into writing or art one day.”

Yang spent more time at the symposium discussing his writing process than he did at the other events: he described how he started writing comic books during his middle school years, and how he manufactured his own comics prior to getting a writing deal for American Born Chinese.

“I would do a chapter at home, I would take it to my local photocopy store, I would run off a whole lot of copies, I stapled them by hand, and I would sell them,” said Yang. “There was a local comic book store that was willing to sell handmade comics, and I would take them to local comic book conventions. I would rent a table, and I would sell them from this table. At the end of the day, I would sell maybe twelve comics, and it would be like ten of my friends, one stranger, and my mom.”

This information regarding comic book creation was a key part of the presentation for some students, who came to learn from the author. This included Bates, who said she attended the symposium to learn more about writing comics and graphic novels.

“I want to be a comic book artist or author in the future, and it was a good opportunity to find out about that,” Bates said.

Park hopes that hearing Yang speak, as well as reading the novel in class, will inspire students, and help them be more accepting of themselves and others.

“I think the messages of the novel, that we are all worthy and powerful and important just the way we are, without sacrificing our selfhoods for “normalcy,” without giving up some of our soul to become liked or more popular, are so critical for teenagers as they decide who they want to be,” said Park. “Adolescence is a time when people figure out what their identity means in a much bigger way, and I think the novel connects teens to critical messages for their own identity development in ways that aren’t always effectively communicated in school.”

Want to help the Herd? Please consider supporting the Periscope program. Your donation will support the student journalists of CHS and allow us to purchase equipment, send students to workshops/camps, and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Samantha Martin is super excited to share the role of Editor-in-Chief with Abigail Lindsay during her fourth year on staff! She is also a member of several...

Keely McGeehan • Nov 19, 2019 at 1:19 pm

Thank you for writing such a lovely article to capture Yang’s time on campus and the impact he had on our students! It really was a terrific experience!